Indian Subcontinent

One and a half million volunteers came forward from the estimated population of 315 million in the Indian subcontinent (present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka – henceforth referred to, for convenience, as 'India').

Of these 140,000 saw active service on the Western Front in France and Belgium – 90,000 in the front-line Indian Corps, and some 50,000 in auxiliary battalions. Indians were in action on the Western Front within a month of the start of the war, at the First Battle of Ypres where Khudadad Khan became the first Indian to win a Victoria Cross. After a year of front-line duty, sickness and casualties had reduced the Indian Corps to the point where it had to be withdrawn. Nearly 700,000 then served in the Middle East, fighting with great distinction against the Turks in the Mesopotamian campaign. Indians served on the Gallipoli peninsula, and others went to East and West Africa, and even to China.

Participants from the Indian subcontinent won 13,000 medals, including 12 Victoria Crosses. By the end of the war a total of 47,746 Indians had been reported dead or missing; 65,126 were wounded.

Some 100,000 Gurkhas from Nepal took part in fighting during the First World War. Two Victoria Crosses – the supreme award for valour – were won by Gurkhas.

Of these 140,000 saw active service on the Western Front in France and Belgium – 90,000 in the front-line Indian Corps, and some 50,000 in auxiliary battalions. Indians were in action on the Western Front within a month of the start of the war, at the First Battle of Ypres where Khudadad Khan became the first Indian to win a Victoria Cross. After a year of front-line duty, sickness and casualties had reduced the Indian Corps to the point where it had to be withdrawn. Nearly 700,000 then served in the Middle East, fighting with great distinction against the Turks in the Mesopotamian campaign. Indians served on the Gallipoli peninsula, and others went to East and West Africa, and even to China.

Participants from the Indian subcontinent won 13,000 medals, including 12 Victoria Crosses. By the end of the war a total of 47,746 Indians had been reported dead or missing; 65,126 were wounded.

Some 100,000 Gurkhas from Nepal took part in fighting during the First World War. Two Victoria Crosses – the supreme award for valour – were won by Gurkhas.

Personal story: Khudadad Khan VC

Sepoy Khudadad Khan VC, 129th Battalion, Duke of Connaught's Own Baluchi Regiment

Sepoy Khudadad Khan VC, 129th Battalion, Duke of Connaught's Own Baluchi Regiment

Khudadad Khan was born in the Punjab (now in Pakistan) in 1887. His family were Pathans who had moved to the Punjab from the North-West Frontier between India and Afghanistan. He joined the army as a sepoy or private soldier for the sake of regular pay and a chance of honour and glory. In October 1914, almost immediately after arriving in France, the 129th Baluchis were among 20,000 Indian soldiers sent to the front line. Their job was to help the exhausted and depleted soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to prevent the advancing Germans from capturing the vital ports of Boulogne in France and Nieuwpoort in Belgium. If the Germans could manage to take Boulogne and Nieuwpoort, they would choke off the BEF'S supplies of food and ammunition, and the Allies would lose the war.

The 129th Baluchis, with whom Khudadad Khan was serving as a machine-gunner, faced the well-equipped German army in appalling conditions – shallow waterlogged trenches in which to take cover, a lack of hand grenades and barbed wire, and a dire shortage of soldiers to man the defensive line. They were also outnumbered five to one. When the Germans attacked on 30 October, most of the Baluchis were pushed back. But Khudadad Khan's machine-gun team, along with one other, fought on, preventing the Germans from making the final breakthrough. The other gun was disabled by a shell, and eventually Khudadad Khan's own team was over-run. All the gunners were killed by bullets or bayonets except the badly wounded Khudadad Khan. He pretended to be dead until the attackers had gone on – then, despite his wounds, he managed to make his way back to his regiment. Thanks to his bravery, and that of his fellow Baluchis, the Germans were held up just long enough for Indian and British reinforcements to arrive. They strengthened the line, and prevented the German army from reaching the vital ports.

Sepoy Khudadad Khan recovered from his wounds in an English hospital, and three months later was decorated by King George V at Buckingham Palace in London with the Victoria Cross, Britain's highest award 'For Valour'. He was the first Indian to receive the award. Khudadad Khan returned to India, and continued to serve in the Indian Army. In 1971 he died at home in Pakistan, aged 84.

The 129th Baluchis, with whom Khudadad Khan was serving as a machine-gunner, faced the well-equipped German army in appalling conditions – shallow waterlogged trenches in which to take cover, a lack of hand grenades and barbed wire, and a dire shortage of soldiers to man the defensive line. They were also outnumbered five to one. When the Germans attacked on 30 October, most of the Baluchis were pushed back. But Khudadad Khan's machine-gun team, along with one other, fought on, preventing the Germans from making the final breakthrough. The other gun was disabled by a shell, and eventually Khudadad Khan's own team was over-run. All the gunners were killed by bullets or bayonets except the badly wounded Khudadad Khan. He pretended to be dead until the attackers had gone on – then, despite his wounds, he managed to make his way back to his regiment. Thanks to his bravery, and that of his fellow Baluchis, the Germans were held up just long enough for Indian and British reinforcements to arrive. They strengthened the line, and prevented the German army from reaching the vital ports.

Sepoy Khudadad Khan recovered from his wounds in an English hospital, and three months later was decorated by King George V at Buckingham Palace in London with the Victoria Cross, Britain's highest award 'For Valour'. He was the first Indian to receive the award. Khudadad Khan returned to India, and continued to serve in the Indian Army. In 1971 he died at home in Pakistan, aged 84.

Personal story: Manta Singh

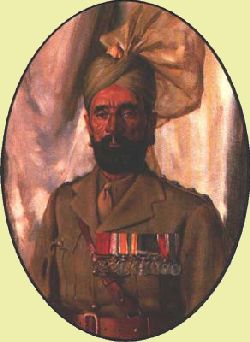

Subedar Manta Singh: 2nd Sikh Royal Infantry

Subedar Manta Singh: 2nd Sikh Royal Infantry

Manta Singh was born in the Punjab, northern India. In 1907, as soon as he left the village school, he joined the 2nd Sikh Royal Infantry. By August 1914, when the German army invaded Belgium and France, Manta held the rank of Subedar, and his regiment was part of the Indian Expeditionary Force sent to France.

In March 1915 the Allies attacked Neuve-Chapelle and broke through the German front line. On the first day of the battle, British and Indian troops captured the town. Then the Germans counter-attacked with 16,000 reinforcements. In three days' fighting, the British and Indian troops suffered 13,000 casualties. The Allies' ammunition ran out, and the troops had to retreat. 5,021 Indian soldiers – about 20 per cent of the Indian contingent – were killed in heavy fighting, and Manta Singh was injured in action after helping to save the life of an injured officer, Captain Henderson. (In the Second World War, the sons of both of these men served side by side and became lifelong friends.)

Manta Singh was sent back to England, to a hospital in Brighton. The doctors told him that he would have to lose both his legs, as they had become infected with gangrene. Manta refused to think about going back to India with no legs – what use would he be to his family? Unfortunately, he died from blood poisoning a few weeks later. He was cremated in a ghat, according to Sikh beliefs.

In 1993 Manta Singh's son, Lt Col Assa Singh Johal, was part of a delegation of the Undivided Indian Ex-Servicemen's Association that visited the Indian war memorial at Neuve-Chapelle. Assa Singh said, "It was a moving visit of great sentimental value to us. We were able to remember and pay homage to the fallen in foreign lands."

In March 1915 the Allies attacked Neuve-Chapelle and broke through the German front line. On the first day of the battle, British and Indian troops captured the town. Then the Germans counter-attacked with 16,000 reinforcements. In three days' fighting, the British and Indian troops suffered 13,000 casualties. The Allies' ammunition ran out, and the troops had to retreat. 5,021 Indian soldiers – about 20 per cent of the Indian contingent – were killed in heavy fighting, and Manta Singh was injured in action after helping to save the life of an injured officer, Captain Henderson. (In the Second World War, the sons of both of these men served side by side and became lifelong friends.)

Manta Singh was sent back to England, to a hospital in Brighton. The doctors told him that he would have to lose both his legs, as they had become infected with gangrene. Manta refused to think about going back to India with no legs – what use would he be to his family? Unfortunately, he died from blood poisoning a few weeks later. He was cremated in a ghat, according to Sikh beliefs.

In 1993 Manta Singh's son, Lt Col Assa Singh Johal, was part of a delegation of the Undivided Indian Ex-Servicemen's Association that visited the Indian war memorial at Neuve-Chapelle. Assa Singh said, "It was a moving visit of great sentimental value to us. We were able to remember and pay homage to the fallen in foreign lands."